I don't know if I've mentioned before that I hate

Umberto Eco's writing style - if it hadn't been for Sean Connery and Christian Slater, I'd still not know what

The Name of the Rose was about :) But recently, I've realized he's also a philosopher with some interesting stuff on

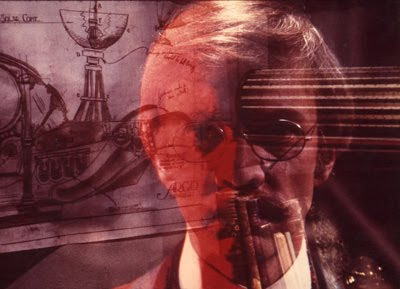

semiotics, so when I "saw" him twice this week, I thought I'd post about the sightings .....

First, I cam across this story in the Telegraph -

Don't blame Silvio Berlusconi, says Umberto Eco, it's the fault of all Italians. But more interesting, I later saw reference to a series of letters he exchanged with

Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini back in the late 90s and run in an Italian newspaper (also a book -

Belief or nonbelief?: a confrontation by Umberto Eco, Carlo Maria Martini). Many topics were discussed, including the question of when life begins, and the end of the world. I did find one of Eco's letters from the discussion at

Cross Currents. Here it is below ....

*************************************

WHEN THE OTHER APPEARS ON THE SCENE

by Umberto Eco

This article is derived from an exchange of four letters with Cardinal Martini. The following letter is Eco’s reply to a question the cardinal had asked him: “What is the basis of the certainty and necessity for moral action of those who, in order to establish the absolute nature of an ethic, do not intend to appeal to metaphysical principles or transcendental values, or even to universally valid categorical imperatives?”

— The EditorsDear Carlo Maria Martini,

Your letter has extricated me from one serious dilemma only to leave me on the horns of another that is equally awkward. Until now it has been up to me (through no decision of mine) to open the debate, and he who talks first inevitably puts his questions and invites the other to reply. My predicament springs from my feeling inquisitorial. And I very much appreciated the firmness and humility with which you, on three occasions, exploded the myth that would have us believe that Jesuits always answer a question with another question.

But now I am at a loss as to how to reply to your question, because my answer would be significant had I had a lay upbringing. But in fact I received a strongly Catholic education until (just to record the moment of the breach) the age of twenty-two. For me, the lay point of view was not a passively absorbed heritage, but rather the hard-won result of a long and slow process of change, and I always wonder whether some of my moral convictions do not still depend on religious impressions received early in my development. Now, in my maturity, I have seen (in a foreign Catholic university that also employs lay teaching staff, requiring of them no more than a manifestation of formal respect during religious-academic rituals) some of my colleagues take the sacraments without their believing in the Real Presence, and therefore without their having taken confession beforehand. With a tremor, after so many years, I felt once more the horror of sacrilege.

Nonetheless, I feel I can explain the foundations on which my “lay religiosity” rests—because I firmly hold that there are forms of religiosity, and therefore a sense of the Holy, of the Limit, of questioning and of awaiting, of communion with something that transcends us, even in the absence of faith in a personal and provident divinity. But, as I see from your letter, you know this too. What you are asking yourself is what is binding, captivating, and inalienable in these forms of ethic.

I should like to approach things in a roundabout way. Certain ethical problems became clearer to me on considering some problems in semantics—and please don’t worry if some people say that we are talking in a complicated way: they might have been encouraged to think too simply by mass-media “revelations,” predictable by definition. Let them instead learn to “think complicated,” because neither the mystery nor the evidence is simple.

My problem hinged on the existence of “semantic universals,” or in other words, elementary notions that are common to the entire human species and can be expressed in all languages. Not such an easy problem, given that many cultures do not recognize notions that strike us as obvious: for example, that of substance to which certain properties belong (as when we say that “the apple is red”) or that of identity (a=a). However, I am convinced that there certainly are notions common to all cultures, and that they all refer to the position of our body in space.

We are erect animals, so it is tiring to stay upside down for long, and therefore we have a common notion of up and down, tending to favor the first over the second. Likewise, we have notions of right and left, of standing still and of walking, of standing up and lying down, of crawling and jumping, of waking and sleeping. Since we have limbs, we all know what it means to beat against a resistant material, to penetrate a soft or liquid substance, to crush, to drum, to pummel, to kick, and perhaps even to dance as well. The list is a long one, and could include seeing, hearing, eating or drinking, swallowing or excreting. And certainly every human being has notions about the meaning of perceiving, recalling, feeling, desire, fear, sorrow, relief, pleasure or pain, and of emitting sounds that express these things. Therefore (and we are already in the sphere of rights) there are universal concepts regarding constriction: we do not want anyone to prevent us from talking, seeing, listening, sleeping, swallowing, or excreting, or from going where we wish; we suffer if someone binds or segregates us, beats, wounds, or kills us, or subjects us to physical or psychological torture that diminishes or annuls our capacity to think.

Note that until now I have described only a sort of bestial and solitary Adam, who still knows nothing of sexual relations, the pleasures of dialogue, love for his offspring, or the pain of losing a loved one; but already in this phase, at least for us (if not for him or for her) this semantics has become the basis of an ethic: first and foremost we must respect the rights of the corporeality of others, which also include the right to talk and think. If our fellows had respected these “rights of the body,” we would never have had the Slaughter of Innocents, the Christians in the circus, Saint Bartholomew’s Night, the burning of heretics, the death camps, censorship, child labor in mines, or the rapes in Bosnia.

But how is it that this marveling and ferocious beast that I have described immediately works out his (or her) instinctive repertoire of universal notions and can reach the point where he understands not only that he wishes to do certain things and does not wish other things to be done to him, but also that he should not do to others what he does not wish to be done to him? Because, luckily, Eden is soon populated. The ethical dimension begins when the other appears on the scene. Every law, moral or juridical as it may be, regulates interpersonal relationships, including those with an other who imposes that law.

You too say that virtuous laypersons are persuaded that the other is within us. However, this is not a vague emotional inclination but a fundamental condition. As we are taught by the most secular of human sciences, it is the other, it is his look, that defines and forms us. Just as we cannot live without eating or sleeping, we cannot understand who we are without the look and response of the other. Even those who kill, rape, rob, or oppress do this in exceptional moments, but they spend the rest of their lives soliciting from their fellows approval, love, respect, and praise. And even from those they humiliate they ask the recognition of fear and submission. In the absence of this recognition, the newborn baby abandoned in the forest does not become humanized (or like Tarzan seeks at all costs the other in the face of an ape), and the result of living in a community in which everyone had decided systematically never to look at us, treating us as if we did not exist, would be madness or death.

Why is it then that there are or have been cultures that approve of massacre, cannibalism, or the humiliation of the bodies of others? Simply because such cultures restrict the concept of “others” to the tribal community (or the ethnic group) and consider “barbarians” to be nonhumans; but not even the Crusaders felt that unbelievers were fellowmen worthy of an excessive degree of love. The fact is that the recognition of the roles of others, the necessity to respect in them those requirements we consider essential for ourselves, is the product of thousands of years of development. Even the Christian commandment to love was enunciated, and laboriously accepted, only when the time was ripe.

But you ask me: Is this awareness of the importance of the other sufficient to provide us with an absolute basis, an immutable foundation for ethical behavior? It would suffice for me to reply that even those things that you define as “absolute foundations” do not prevent many believers from knowingly sinning, and there the matter would end. The temptation of evil is present even in those who possess a well-founded and revealed notion of good. But I want to tell you two anecdotes, which gave me much to think about.

One concerns a writer, who describes himself as a Catholic, albeit of the sui generis variety, whose name I shall not give only because he told me what I am about to quote in the course of a private conversation, and I am not a talebearer. It was in the days of the papacy of John XXIII, and my elderly friend, in enthusiastically praising the pope’s virtues, said (with clearly paradoxical intentions): “Pope John must be an atheist. Only a man who does not believe in God can love his fellowman so much!” Like all paradoxes, this one also contains a grain of truth: without troubling to consider the atheist (a type whose psychology eludes me, because, as Kant observed, I do not see how one can not believe in God, and hold that His existence can not be proved, and then firmly believe in the nonexistence of God, holding that it can be proved), it seems clear to me that a person who has never had any experience of the transcendent, or who has lost it, can make sense of his or her life and death, can be comforted by love for others, and by the attempt to guarantee someone else a life to be lived even after his or her own death. Of course, there are people who do not believe and nonetheless do not trouble to make sense of their own death, but there are also those who say they believe but who would be prepared to rip the heart out of a child in order to ward off death. The strength of an ethic is judged on the behavior of saints, not on the foolish cujus deus venter est.

This brings me to the second anecdote. I was still a sixteen-year-old Catholic boy when I happened to cross swords in a verbal duel with an older acquaintance who was a known “communist,” in the sense in which the term was employed in the terrible fifties. And since he was provoking me, I asked him the decisive question: how could he, as a nonbeliever, make sense of that otherwise senseless event that was his own death? And he replied: “By asking before dying that I might have a civil funeral. And so I am no more, but I have set an example for others.” I think that you too can admire the profound faith in the continuity of life, the absolute sense of duty that inspired his reply. And it is this sentiment that has induced many nonbelievers to die under torture rather than betray their friends, and others to catch the plague in order to look after plague victims. And sometimes it is also the only thing that drives a philosopher to philosophize, and a writer to write: to leave a message in the bottle, because in some way what we believe in, or what we think is beautiful, might be believed in or found beautiful by posterity.

Is this feeling really strong enough to justify an ethic as determined and inflexible, as solidly established as the ethic of those who believe in revealed morality, in the survival of the soul, in reward and punishment? I have tried to base the principles of a lay ethics on a natural reality (and, as such, in your view too, the result of a divine plan) like our corporeality and the idea that we instinctively know that we have a soul (or something that serves as such) only by virtue of the presence of others. It would appear that what I have defined as a “lay ethics” is at bottom a natural ethics, which not even believers deny. Is not the natural instinct, brought to the right level of maturity and self-awareness, a foundation offering sufficient guarantees? Of course we may think this an insufficient spur to virtue. “In any case,” nonbelievers can say, “no one will know of the evil I am secretly doing.” But those who do not believe think that no one is watching them from on high, and therefore they also know that—precisely for this reason— there is not even a Someone who may forgive. If such people know they have done ill, their solitude shall be without end, and their death desperate. They will opt, more than believers, for the purification of public confession, they will ask the forgiveness of others. This they know, in the deepest part of their being, and therefore they know that they should forgive others first. Otherwise how could we explain that remorse is a feeling known to nonbelievers too?

I should not like to establish a clear-cut opposition between those who believe in a transcendent God and those who believe in no superindividual principle. I should like to point out that it was precisely ethics that inspired the title of Spinoza’s great work, which begins with a definition of God as the cause of Himself. But Spinoza’s divinity, as we well know, is neither transcendent nor personal: yet even the vision of a great and single cosmic

substance in which one day we shall be reabsorbed can reveal a vision of tolerance and benevolence precisely because we are all interested in the equilibrium and harmony of this sole

substance. This is so because we tend to think it impossible for this substance not to be in some way enhanced or deformed by the things we have done over the millennia. Thus I would also dare say (this is not a metaphysical hypothesis, it is merely a timid concession to the hope that never abandons us) that even from such a standpoint we could table the problem of some kind of life after death. Today the electronic universe suggests that sequences of messages can be transferred from one physical medium to another without losing their unique characteristics, and it seems that they can exist even as pure immaterial algorithms when, one medium have been abandoned, they are not transcribed again onto another. And who knows whether death, rather than an implosion, is not an explosion and the impressing, somewhere, among the vortices of the universe, of the software (which others call “soul”) we have developed in life, made up of memories and personal remorse, and therefore of incurable suffering, or of a sense of peace for duty done, and love.

But you say that, without the example and the word of Christ, all lay ethics would lack a basic justification imbued with an ineluctable power of conviction. Why deprive laypersons of the right to avail themselves of the example of a forgiving Christ? Try, Carlo Maria Martini, for the good of the discussion and of the dialogue in which you believe, to accept even if only for a moment the idea that there is no God; that man appeared in the world out of a blunder on the part of maladroit fate, delivered not only unto his mortal condition but also condemned to be aware of this, and for this reason the most imperfect of all creatures (if I may be permitted the echoes of Leopardi in this suggestion). This man, in order to find the courage to await death, would necessarily become a religious animal, and would aspire to the construction of narratives capable of providing him with an explanation and a model, an exemplary image. And among the many stories he imagines—some dazzling, some awe-inspiring, some pathetically comforting—in the fullness of time he has at a certain point the religious, moral, and poetic strength to conceive the model of Christ, of universal love, of forgiveness for enemies, of a life sacrificed that others may be saved. If I were a traveler from a distant galaxy and I found myself confronted with a species capable of proposing this model, I would be filled with admiration for such theogonic energy, and I would judge this wretched and vile species, which has committed so many horrors, redeemed were it only for the fact that it has managed to wish and to believe that all this is the truth.

You are now free to leave the hypothesis to others: but admit that even if Christ were only the subject of a great story, the fact that this story could have been imagined and desired by humans, creatures who know only that they do not know, would be just as miraculous (miraculously mysterious) as the son of a real God’s being made flesh. This natural and worldly mystery would not cease to move and ennoble the hearts of those who do not believe.

This is why I believe that, on the fundamental points, a natural ethic— respected for the profound religiosity that inspires it—can find common ground with the principles of an ethic founded on faith in transcendence, which cannot fail to recognize that natural principles have been carved into our hearts on the basis of a plan for salvation. If this leaves, as it certainly does, margins that may not overlap, it is no different from what happens when different religions encounter one another. And in conflicts of faith,

charity and

prudence must prevail.

**************************

.jpg)