-

Christ Blessing the Little Children - William Blake

Part of the gospel readings for today from Matthew ...

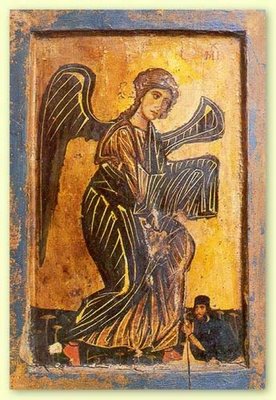

And people were bringing children to him that he might touch them, but the disciples rebuked them. When Jesus saw this he became indignant and said to them, "Let the children come to me; do not prevent them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these. Amen, I say to you, whoever does not accept the kingdom of God like a child will not enter it." Then he embraced them and blessed them, placing his hands on them.I've never really understood this, though I've read many interpretations. Below is one of those interpretations, which relies on the writings of

Hans Urs von Balthasar, in an article -

Becoming Children: The Hidden Meaning of the Incarnation by Nick Trakakis, Department of Philosophy at Monash University - from the Theandros Journal. I've posted much (but not all) of the article below, and added the footnotes too ...

*************************

... how do we, who are either well on our way towards adulthood or firmly established as adults, suddenly stop and return to the mind-set and attitudes of our beginnings? Why, even, would we want to make such a turnabout in the first place? Children are, of course, very often endearing creatures, but they do not always manifest the best qualities of human nature: they can be quite cruel to each other, they are supremely self-centred, they can barely think beyond the present or the present satisfaction of their needs, they live a sheltered and heavily protected existence, they are gullible, and so on. Why, then, should we want to become like children, and what does becoming a child actually involve?

The eminent Roman Catholic theologian, Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988), in his short but insightful book

Unless You Become Like This Child, provides a searching discussion of these questions.[1] Von Balthasar points out that there are several things involved in the process that Jesus referred to as becoming like children, three of which I think are worthy of some reflection.

Firstly, the exhortation to become like children is to be understood in terms of the call to recover our childlike gratitude. Such gratitude, as von Balthasar explains, is reflected in the words and actions of Jesus, ‘the eternal Child’: "Thanksgiving, in Greek eucharistia, is the quintessence of Jesus’ stance toward the Father. ‘Father, I thank you for having heard me’, he says at Lazarus’ grave, conscious that the Father has given him the power to raise the dead (Jn 11:41)."[2] Children, likewise, are thankful for the gifts that are freely bestowed on them by their parents, whether it be food, clothing, protection, or Christmas presents. But as von Balthasar notes, plea and thanks in a child, the child’s dependency and its gratitude, cannot yet be clearly distinguished: "Because he [i.e., the child] is needy he is also thankful in his deepest being, before making any free, moral decision to be so. And when he grows older and we say to him, ‘Say

please’, ‘say thank you’, we are not teaching him anything new but only trying to bring into his more conscious sphere what is already present from the beginning."[3]

Secondly, becoming like children involves recovering our childlike awe, our childlike sense of amazement. The ancients, it will be recalled, sought to ground their philosophical reflections in a sense of wonder, a wonder rooted in the experience of beauty.[4] This sense of wonder is also an integral part of childhood. Children are often amazed over everything that we take to be ordinary. A child, for example, will be overawed by all the things, great and small, that he discovers in his newly inhabited world, from the tiny insects he spots on the pavement to the starry heavens above. Unfortunately, this appreciation for the wondrous and mysterious qualities of life can be easily lost, as von Balthasar points out: "In the world of men, childlike amazement is not easy to preserve since so much in education aims at learning habits, mastering tasks and grasping automatic functions."[5] The problem is further exacerbated in western capitalist countries, where the emphasis on scientific inquiry and economic productivity, together with sprawling cities and the consequent alienation from the natural environment, quickly sap one’s ability to marvel at the splendour of the world.

Thirdly, becoming like children also means recovering our childlike attitude towards time. Unconsciously, and sometimes even quite consciously, we think that ‘My time is my own’. Our sense of ownership in general, but particularly as it relates to time, is perceptively analysed by C.S. Lewis in his

Screwtape Letters. In letter 21, the demon Screwtape instruct his nephew Wormwood on how to go about inculcating feelings of possessiveness in his human ‘patient’:

Let him have the feeling that he starts each day as the lawful possessor of twenty-four hours. Let him feel as a grievous tax that portion of this property which he has to make over to his employers, and as a generous donation that further portion which he allows to religious duties. But what he must never be permitted to doubt is that the total from which these deductions have been made was, in some mysterious sense, his own personal birthright.[6]

However, the assumption that ‘My time is my own’ is an entirely absurd one, for as Lewis points out (through the mouthpiece of Screwtape), a man "can neither make, nor retain, one moment of time; it all comes to him by pure gift; he might as well regard the sun and moon as his chattels."[7] We are nonetheless led to feel a sense of ownership, not only towards time but towards all things. As Screwtape explains to his nephew, this is the result of both pride and confusion:

We [i.e, the demons] teach them [i.e., the humans] not to notice the different senses of the possessive pronoun – the finely graded differences that run from ‘my boots’ through ‘my dog’, ‘my servant’, ‘my wife’, ‘my father’, ‘my master’ and ‘my country’, to ‘my God’. They can be taught to reduce all these senses to that of ‘my boots’, the ‘my’ of ownership… We have taught men to say ‘my God’ in a sense not really very different from ‘my boots’, meaning ‘the God on whom I have a claim for my distinguished services and whom I exploit from the pulpit – the God I have done a corner in’.[8]

Such a possessive attitude towards God and time is completely alien to the person who has recovered their childlikeness. As von Balthasar eloquently puts it, "The child has time to take time as it comes, one day at a time, calmly, without advance planning or greedy hoarding of time. Time to play, time to sleep. He knows nothing of appointment books in which every moment has been sold in advance."[9] However, von Balthasar is quick to add that he does not mean to endorse an idle way of life where one’s time is squandered "like cheap merchandise". Rather, his point is that "we should live the time that is given us now, in all its fullness", where this is not to be reduced to such contemporary slogans as ‘enjoying life to the full’ or ‘making the most of it’. The point, rather, is "only that we should receive with gratitude the full cup that is handed to us."[10]

Only when we look upon time in this way, argues von Balthasar, can we find God in all things. In words that might resonate deeply with many of us, he writes: "Pressured man on the run is always postponing his encounter with God to a ‘free moment’ or a ‘time of prayer’ that must constantly be rescheduled, a time that he must laboriously wrest from his overburdened workday. A child that knows God can find him at every moment because every moment opens up for him the very ground of time: as if it reposed on eternity itself."[11] ......

Notes:

[1] Hans Urs von Balthasar,

Unless You Become Like This Child, transl. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991). The German original was published in 1988 as Wenn ihr nicht werdet wie dieses Kind.

[2] Von Balthasar,

Unless You Become Like This Child, pp.47-48.

[3] Ibid., p.49.

[4] The principal text in this connection is to be found in lines 155c-d of Plato’s

Theatetus, where Plato has Socrates say, "This feeling – a sense of wonder – is perfectly proper to a philosopher: philosophy has no other foundation, in fact" (trans. Robin A.H. Waterfield, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1987, p.37).

[5] Von Balthasar,

Unless You Become Like This Child, p.46.

[6] C.S. Lewis,

The Screwtape Letters (London: HarperCollins, 1942), p.112.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., p.114.

[9] Von Balthasar,

Unless You Become Like This Child, pp.53-54.

[10] Ibid., p.54.

[11] Ibid., pp.54-55.